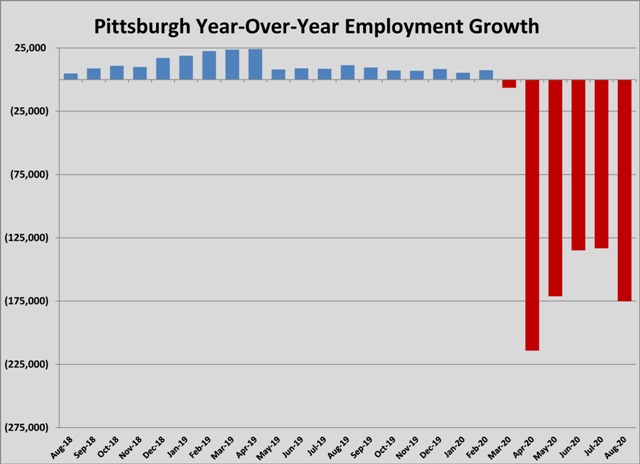

There was a good story in Pittsburgh Quartelry’s digital update this morning on the region’s unemployment rate. Check out Julia’s Fraser’s story. The top line was good news. The unemployment rate fell from 12.8% in July to 10.5% in August. But the data was less rosy. The actual number of people employed fell by 39,405 from July to August; and the year-over-year decline in total employment plunged to more than 175,000. That’s the worst year-over-year decline since April 2020, and the second worst decline since the recession began in February. In part, that’s because August 2019 marked a high point in regional employment, with 1,157,274 people employed. However, the year-over-year decline jumped because the economy in Pittsburgh has weakened further with the end of the Payroll Protection Program.

These two concepts may seem at odds. How can unemployment drop more than two points when employment drops by almost four points? Remember, the unemployment rate is just the math. It’s easy to forget that if the total number of people in the workforce decline, the unemployment rate will decline (assuming the number of jobs lost doesn’t outstrip the number of people leaving the workforce). That’s what happened in August. While unemployment rose by 74,800 compared to August 2019 (or 6.5 points), the workforce declined by 48,000 people. It’s the latter number that is a key metric that we don’t understand at the moment. Pittsburgh Quarterly quotes Pitt’s Chris Briehm on the subject and he notes quite correctly that we won’t know the full story until the public health crisis ends.

It’s worth digging into that a bit. Briehm’s point is that the varying motives of people leaving the workforce during a pandemic make it impossible to judge whether or not there is an accelerating trend towards a smaller workforce. Unemployment insurance allows some people who can’t work remotely to not work, rather than take the risk of infection. Others will take the choice of unemployment over illness, even if they don’t qualify for UI. Still others who must work – like in restaurants or bars – may have chosen to relocate to states where those establishments have reopened to a greater degree than in Pennsylvania. And some of the workers have quit looking for work for now or have chosen to retire. Until there is clarity about the safety of the workplace, we won’t know how many of the workers who left the workforce are coming back; and until there is organic job growth, meaning adding of new positions, we won’t know how much of the discouraged workforce will return.

The significance of a declining workforce is obscured in a severe jobs recession like we’ve seen since March. For now, at least, the decline has positive benefits. Fewer people are looking for work. Pittsburgh’s unemployment rate is lower, even though the number of employed is much lower. If the people who have declared themselves as out of the workforce in August remain out, that means unemployment is not artificially low. That’s a good thing. But, if that’s true, then Pittsburgh faces a much bigger uphill battle once economic growth returns. Employers will struggle to find workers with the skills they need. Growing companies can’t tolerate that, so they will look elsewhere for talent. That means some will close shop in Pittsburgh and move elsewhere, or expand elsewhere instead of Pittsburgh. The region’s future is predicated on the innovation economy driving job growth in Pittsburgh. That can’t happen if innovators can’t find employees in Western PA. Our vaunted university research does Pittsburgh no good if the businesses that spin out of them move to Palo Alto or Austin or Nashville. Let’s hope that the cure for the public health crisis results in a cure for our workforce decline as well.